There are five key facts controlling the state of digital media business in the twenty-first century, and content providers ignore them at their peril. Through a deep understanding of these fundamental realities, Glyder is building powerful solutions to achieve two primary objectives:

Enable online content providers to generate much better revenue to sustain the production of quality content.

Give consumers much better access: faster, easier, more secure and more affordable access to more paywall content.

Quick Links to the Five Key Facts

Exhibit A: News Media

Below is a summary of the five key facts, and we’ll use newspapers and online news media as a lens through which to understand them.

Why news?

Newspapers are suffering enormously from an ongoing revenue crisis as they transition from print to digital, but they are just the tip of the iceberg. Online news media’s revenue problems are the same problems now emerging for virtually all media struggling to establish viable online and mobile content business practices. Understanding and addressing the serious problems facing news media will go a long way toward solving the complex problems plaguing all online content.

1. All Current Revenue Models Are Failing

Looking at online news media as an indicator of broader trends, there is no word for current revenue practices other than “failure.” It is important that we acknowledge and understand this failure if we are going to build something that actually works.

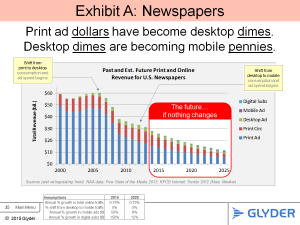

Print Revenue Failure

While we are primarily interested in examining what is happening with online revenue, it is important to recognize that news media is transitioning from a failing print revenue model to an additionally failing online model. That context makes the need for better online revenue all the more urgent.

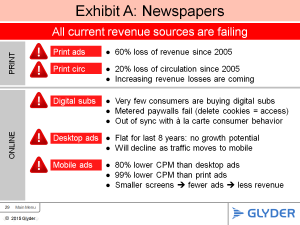

60% loss of print ad revenue since 2005.

20% decline in print circulation since 2005.

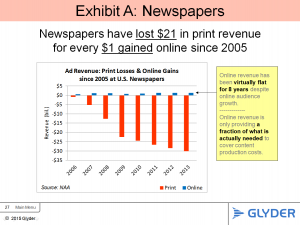

$21 lost in print revenue for every $1 gained in new online revenue.

Further losses in advertising and circulation revenue will continue for the foreseeable future.

Online Revenue Failure

Digital Subscriptions Failure

Very few consumers are buying digital subscriptions.

Less than 2% (and by some estimates, less than 1%) of the people reading online news content have paid for that content.

Metered paywalls are technical failures: by regularly deleting their browser cookies, consumers can obtain unlimited access to virtually every metered paywall site that exists.

The online subscription concept is fundamentally out of sync with consumer preferences and behavior. (See sections #3 and #4 below.)

Desktop Ad Revenue Failure

Online ad revenue has been minimal and, for all practial purposes, virtually flat for the last 8 years, despite surging growth in online traffic. Substantial ad revenue growth is highly unlikely. (See the charts below.)

Advertisers pay next to nothing for online ad space because there is already an overcapacity of space and insufficient ad dollars to fill it. Further, consumer engagement with online advertising is terrible. It’s not unreasonable for advertisers to conclude that they are already over-paying for what they get. Are they going to pay higher rates? Unlikely.

Desktop ad revenue will inevitably decline as traffic and content migrate to mobile. (See section #2 below.)

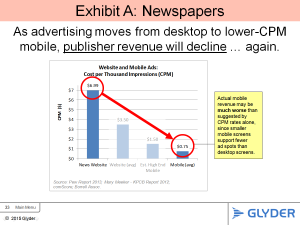

Mobile Ad Revenue Failure

Mobile ad rates are 80% to 90% lower than desktop ad rates, and 99% lower than print ad rates. This might sound great from an advertiser’s perspective (aside from terrible online consumer engagement), but for publishers, this is a disaster. The same content must be produced with 80% to 99% less revenue than before.

Highly negative consumer response to mobile advertising, which eats up a consumer’s limited screen space. Engagement levels are worse than for desktop ads, and enormously worse than print. Will advertisers pay higher rates? Unlikely.

Mobile devices => smaller screens => fewer ads => less revenue.

Consequences

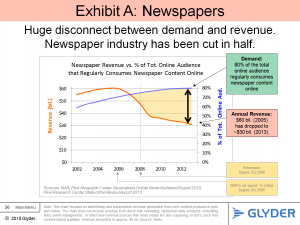

The newspaper industry in print and online has been cut in half: $60B in total annual revenue in 2005 has become ~$30B in 2014, despite surging demand for news content.

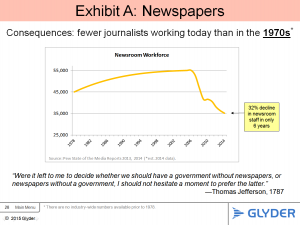

Because revenue has evaporated, staff have been cut, and there are now fewer journalists working today than in the 1970s. Fewer journalists means less original news content, and this undoubtedly impacts society’s ability to remain well informed about issues of public interest.

Charts

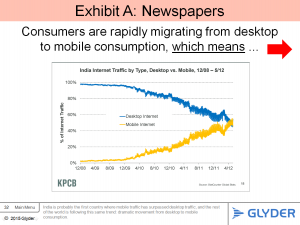

2. As Traffic and Content Migrate to Mobile, Online Revenue Will Decline

The math is inescapable:

Consumers are rapidly migrating from desktop website content to mobile content, and this trend will continue for the foreseeable future. In some parts of the world, mobile traffic has already surpassed desktop traffic.

Mobile ad CPM rates are 80% to 90% lower than desktop website CPM rates.

This means that the minute a consumer moves from browsing content on a laptop to browsing on a smartphone, that publisher’s ad revenue drops by 90% even when it is the same customer consuming exactly the same content. The only thing that changes is the device … and the revenue.

Mobile ad revenue may be even worse than is suggested by CPM ad rates alone, since mobile devices have smaller screens and less real estate for advertising.

Charts

3. The Only Remaining Underutilized Revenue Source Is: Consumers

What? Why are we picking on consumers here? Well, we’re not actually doing that … we love consumers! We are consumers! Without consumers, media would not exist. Consumers are not at fault for poor online revenue — online media is … but we’re getting ahead of ourselves. (We’ll discuss the underlying causes of this problem in section #4 below.)

First, let’s be clear about what we mean by inadequate and underutilized consumer revenue.

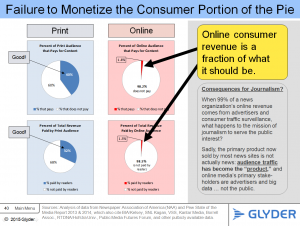

Print: The Audience Is the Primary Guiding Stakeholder

The print media market shows us what consumer engagement and consumer revenue ought to look like. This is a good benchmark for evaluating what is happening with online revenue.

In the print world, 40% of all consumers of news content pay for that content. For example, when one person in a household buys a newspaper, two or three other people typically share it. This is actually a very healthy percentage: content is made available widely and affordably, and advertisers reach ~2.5 people for every newspaper ad they purchase.

One third of the entire publishing budget comes from consumers through single-copy sales and print subscriptions.

Follow the money: Print news publishers can legitimately say that journalism is their primary product, and that it is produced in service to their primary stakeholder — their audience.

Online: The “Audience” Is Becoming the “Product”

In contrast with the print world, online media is a consumer revenue disaster.

Less than 2% of people consuming online news content pay for that content.

Nearly 99% of all online revenue is coming from advertisers.

Consumer revenue supplies only a tiny fraction of what is needed to actually produce the content consumed.

Follow the money: Sadly, the primary product now sold by many online-only news sites is not actually news. Audience traffic data has become the “product,” which is sold to online media’s primary stakeholders: advertisers and big data consumer surveillance firms — not the public.

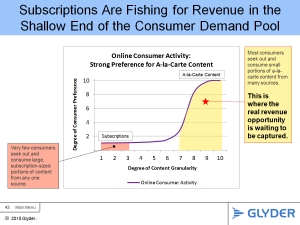

Why Are Subscriptions Not the (Only) Answer?

Subscriptions are a highly appealing idea, but they are unfortunately almost entirely incompatible with the internet environment and consumer behavior online. Subscriptions made lots of sense in the pre-internet print world, but it is largely wishful thinking by publishers that these will play a significant revenue role online.

The subscription concept is out of sync with consumer behavior. Online consumers take tiny bites from thousands of online sources. The primary unit of consumption is not the subscription.

Metered paywall technology seeking to coerce subscriptions is defective. Deleting browser cookies = unlimited access.

The metered-paywall model offers consumers only extreme choices: Free content versus a bill for — in some cases — hundreds of dollars! Consumers are confronted by this same unreasonable pitch at virtually every website they visit.

Subscription-only paywalls discard interested readership, which undermines the mission of journalism and prevents potential purchases. How many millions of transactions are prevented every day because website paywalls require consumers to buy a full-blown subscription instead of allowing them to buy the single article or product the consumer is actually interested in? There is supply, and there is demand, but no sale!

The online subscription model cannot logically be extended throughout a consumer’s browsing experience.

In 1980, a reader would subscribe to maybe five paper sources delivered to a physical mailbox every month. That’s reasonable.

In 2015, individual consumers seek out and consume small portions of content from hundreds and thousands of sources, and virtually every site visited expects the consumer to set up an account, record all of their personal identification and financial information, and buy a subscription. This is highly unrealistic.

Charts

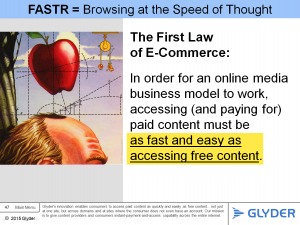

4. What Consumers Require: FASTR Access

If online media must capture better consumer revenue in order to build a sustainable business model, then we must look very carefully at what consumers actually require online … but note that we’re not talking about content here. Media providers already know only too well how to produce high-demand content. The content is not the problem.

What is fundamentally missing is a mechanism of accessing and paying for content that matches consumer behavior.

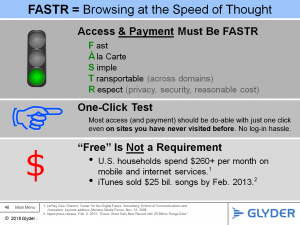

We can summarize the most important consumer requirements with this acronym: FASTR. Note that these requirements apply universally to both paid and free content. It turns out that it is largely irrelevant to the consumer whether content is free or paid! The only thing that is ultimately crucial from a consumer standpoint is whether content access is FASTR.

F = Fast

Consumers require that access to any online content must be fast. The moment anything interferes with nearly immediate access, the consumer moves on to something else.

A = A la Carte

The vast majority of consumers seek out and consume small portions of a-la-carte content from many, many sources. Any content payment and access process must support consumers’ huge preference for a-la-carte consumption.

Almost no one is actively looking to acquire a year’s worth of future content from a single source, and seeking to lock themselves into an ongoing year-long or multi-year payment plan to access that content through an online subscription. It is misguided for publishers to base their consumer revenue strategy on subscriptions alone.

S = Simple

The process used for accessing content must be simple, simple, simple! As with slowness, a complex process used for paying and accessing content sends the consumer elsewhere.

Accessing and paying for paid content should be as fast and easy as accessing free content.

A good test: if access and payment are do-able with a single finger and just a click or two, you are on the right track. If it requires setting up an account, providing credit cards and personal info, logging in or validation email exchanges, forget it — the consumer is gone.

T = Transportable

The 21st century consumer browses widely across hundreds and thousands of websites. Any access or payment process that we expect consumers to use must be capable of working across domains as quickly and easily as that consumer’s own browsing behavior.

Current online revenue practices expect consumers to create separate accounts at every content provider site they visit. This is completely unrealistic, and it disrespects consumers’ time and resources.

R = Respect

Consumers want and deserve respect. They want security regarding their personal and financial information; they want privacy regarding their browsing history; and they want reasonable pricing for the products they consume.

Respect for consumers has been declining rapidly. The current advertising-dominated business model is based largely on stalking consumers as they browse the web, and selling as much of their identity and traffic information as possible to big data advertising brokers. The audience used to be a media company’s most valued stakeholder; now the audience has become the “product,” a commodity sold to advertisers. (See #3 above.)

As consumer revenue increases, media providers should demonstrate greater respect for the consumer’s interests.

Slides

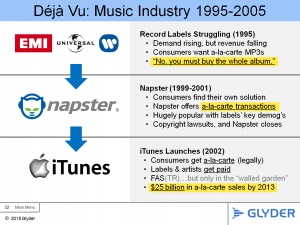

5. Consumers Will Pay for Content When Access and Payment Are FASTR

We now come to the ultimate question. We know that (1) current revenue practices are failing, (2) revenue is declining as traffic migrates from desktop to mobile platforms, (3) consumers are the only remaining underutilized revenue source, and (4) consumers require FASTR access to content.

So, under what conditions will consumers actually pay for content? This is a bit of a trick question, because we have already answered it.

There are several places to see how consumers respond to FASTR (or partially FASTR) access. First, most free content websites meet most of the FASTR requirements: The process of accessing content is Fast, A la Carte, Simple, and Transportable across domains. The Respect component is disappearing from many free and metered paywall sites, but delivering four out of the five FASTR elements is not bad.

To see the FASTR concept applied to paid content, you only have to look at some of the major “walled gardens” of e-commerce: iTunes, Amazon, Google Play. Technically, these sites do not meet all the FASTR elements (falling short in the Transportability and Respect categories), but they illustrate the basic principles. For example, so long as you have an account at iTunes, and are logged into iTunes, and are browsing within iTunes, you can buy a song with a single click — fast, a-la-carte, and simple purchase and access.

Glyder’s technology is revolutionary in that it enables consumers to instantly purchase and access content not just within a “walled garden,” but at virtually any website, including sites where the consumer does not have an account and is not logged in.

Slides

Conclusion

Online content providers are facing one of the most serious challenges in the history of media. Demand for online content is soaring, but all of the current revenue models for supporting the production of quality content are, for all practical purposes, failing.

Online revenue is already insufficient, and the move from desktop to mobile is resulting in further revenue declines, thanks to lower advertising CPM rates and smaller screen sizes, which provide less ad space.

In addition, consumer traffic surveillance, which most media sites have adopted to help pay the bills is corrupting the relationship between media and their audiences. The audience, which was once media’s primary and guiding stakeholder, is rapidly becoming the “product,” a commodity sold to big data.

How is it that consumer demand for online content is growing, but consumer revenue is almost nonexistent? Media companies have built their consumer revenue strategies around a pre-internet, subscription-driven concept, which is completely out of sync with actual consumer behavior. Consumers aren’t looking for subscriptions, so they don’t buy them.

How did we arrive at this impossible situation? Essentially, what has happened is this: We built an extraordinary internet communications system that enables consumers to access content virtually as fast as they can think of it — which is the true genius and beauty of the internet — but we failed to develop a payment mechanism that aligns with that rapid-fire, a-la-carte, cross-domain browsing capability.

Here’s the proof: You can buy a single copy of a newspaper from a newspaper box on the street for a few coins in less than 5 seconds … without logging in, without setting up an account, without revealing all of your personal and financial information. You just pay and go — instantly.

In fact, you could buy a single news “article” in 16th century Venice — which gave birth to the first Western news media system — just as quickly: drop a coin in the box and take the individual article that you want. Done!

Now try doing that online. You can’t! There is something profoundly wrong when it is faster and easier to purchase a-la-carte information on the street (or in 16th century Venice!) than on the internet in the 21st century.

What is fundamentally missing is a mechanism that enables consumers to purchase and access paid content in a way that aligns with their preferred browsing behavior — fast, a-la-carte, wide-ranging consumption of small portions of content from many, many sources.

By grounding our process on the internet’s essential realities and in actual consumer behavior, Glyder enables content providers to generate much better revenue, and enables consumers to have much better access: faster, easier and more affordable access to more paywall content.

This is revolutionary, and it’s about time!

More Info